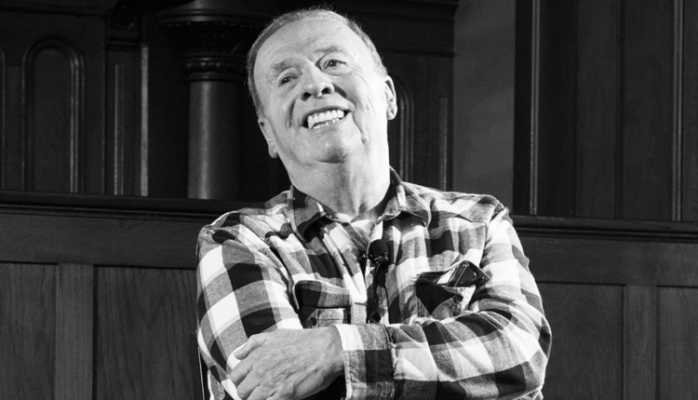

Geoff grew up in Crouch End, north London. Emerick then worked on the Abbey Road album (1969), which brought him a second Grammy. Photograph: Express Newspapers/Getty ImagesĮmerick was not involved in the subsequent bad-tempered sessions for the Let It Be album, but rejoined the Beatles camp when Paul McCartney asked him to rebuild the recording studio at the Beatles’ Apple Corps building in Savile Row, then invited him to engineer The Ballad of John and Yoko, which became the group’s final No 1 single. Geoff Emerick, left, accepting a Grammy award from the Beatles’ drummer, Ringo Starr, in 1968. They were arguing, and I could see the whole thing disintegrating.” “It was something like the eighth attempt at Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da. He worked on further Beatles singles including All You Need Is Love and Lady Madonna, and on the Magical Mystery Tour album, but walked out in the middle of the White Album sessions, frustrated by the group’s arguments and interminable retakes of songs.

The 1967 album won him a Grammy for best engineered recording – non-classical. “The night we put the orchestra on it, the whole world went from black and white to colour,” Emerick said. Thus Emerick became involved in such innovative procedures as chopping up pieces of tape of calliopes and fairground organs for Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite, and recording the orchestral glissandi and colossal “final chord” of A Day in the Life. As they were about to start work on Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Lennon came into the studio and (in Emerick’s words) “said ‘we’re never going to tour again and we’re going to make an album that’s going to have sounds on it that no one’s ever heard before’. “They recorded Maria Callas and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and all these wonderful people … The pop people were like the dregs, except their records paid for the classical sessions.”Īfter the Beatles found that they were unable to replicate the songs from Revolver in live performance, they took the momentous decision to focus solely on studio work. “EMI was classically based at that time,” Emerick recalled. The musical revolution of the Beatles mirrored society’s changes, though it took time to penetrate the staid universe of EMI Records. That he was able to rise to the challenge of this extraordinary track and its mixture of psychedelic mind-expansion and Oriental philosophy (including John Lennon’s famous request for his vocal to sound like “thousands of Tibetan monks chanting on a mountain top”) was an auspicious sign for his future with the quartet, even if, as Emerick said, “to get some of the things on Revolver I had to abuse the equipment, and got into trouble sometimes with the management”.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)